A Matrix of the Habitat Projects

a comparative description of

all the Habitat projects

the conceptual ideas underlying

the Habitat projects

a discussion of the various modular

requirements for each project

the construction techniques specific

to each Habitat project

how the modules were assembled

on their specific sites

the topographical and climatic

factors indigenous to each site

the approaches developed to address

the economic, social and structural

requirements of each site

Habitat ‘67 developed out of architect Moshe Safdie’s 1961 thesis project and report (“A

Case for City Living: An Investigation into the Urban Dwelling for Families”). It was

realized as the main pavilion and thematic emblem for the International World Exposition

and its theme, Man and His World, held in Montreal in 1967. Born of the socialist ideals

of the 1960s, Safdie’s thesis project explored new solutions to urban design challenges and

high-density living. His ideas evolved into a building system which pioneered the

prefabrication and mass-production of modules, called “boxes,” conceived as highly adaptable housing

prototypes for various sites and climatic conditions.

Habitat New York was to have provided luxury, high-density housing and a

full array of commercial, retail, office, and institutional facilities within a

single complex in New York City. The project evolved in two schemes. Designs for

Habitat New York I were undertaken by Safdie between October and December, 1967,

for a waterfront site overlooking the East River, north of the mayor’s

Gracie Mansion in uptown New York City. When the principal backer, Carol

Haussamen, changed the site to a second location on the East River in lower

Manhattan in March, 1968, Safdie developed an entirely new structural system.

The designs for Habitat New York II were developed between May and December,

1968. Neither schemes were realized; Habitat New York was abandoned due to

funding problems.

Funded by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), Habitat Puerto Rico was

commissioned as a prototype for providing low-cost housing to moderate-income

families in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Though unbuilt, the project was

developed in two phases and for two different sites between 1968 and the time of

the project's termination in 1973. Both sites shared similar topographical

features in underdeveloped neighbourhoods of San Juan. Phase I of the project,

designed for the neighbourhood of Hato Rey, evolved in planning stage only

between 1968 and February 1969. This mountainous site was ultimately rejected by

the FHA in favour of a second site, known as Berwin Farm, on which some

preliminary construction did occur between March 1969 and 1973.

When the Israeli Ministry of Housing commissioned Safdie to produce a

prototype for industrialized housing for Israel in 1969, there were specific

design imperatives which needed to be met, and for which Safdie's system of

prefabricated modules seemed perfectly suited. These imperatives stemmed chiefly

from Israel's varied climatic and topographical conditions, as well as its

diverse density requirements (ranging from 10-40 units per acre), owing to the

country's mixed desert and mountain geography. Safdie thus devised a modular

system featuring rotating domes, enabling the resident to transform outdoor

terrace space into an indoor solarium at will. These retractable roofs would

become an integral feature in Safdie's subsequent Israeli projects. This project

is unbuilt.

Habitat Rochester was developed as a

feasibility study for a 1,200-unit residential complex to be sited near downtown

Rochester, New York. Complying with the density requirements and budgetary

constraints of the U.S. Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and the Urban

Development Corporation (UDC), the project’s master plan sought

to combine high-density site requirements with amenable living

conditions for its low- and moderate-income family residents. The project

foresaw community facilities such as daycare centres and commercial stores

within the complex. Unlike any other Habitat projects, Habitat Rochester was

conceived as a cooperative for its residents, who were to partake in aspects of

the project’s initial design process. Moshe Safdie and John Fujiwara

jointly produced the master plan for the project. This project was never

realized.

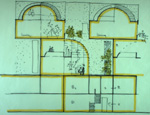

Commissioned by Her Imperial Majesty, the Shahbanou of Iran, Habitat Tehran

was intended to provide high-density, middle- to upper-income housing for

Iranian officials and members of the Shah’s Court in the prestigious

Elahieh neighbourhood of Tehran. Safdie

combined the standard Habitat features of prefabricated, modular housing units

with elements drawn from Iranian culture, notably in the design of an

atrium-court and in the attention to in-coming light within each residence.

Dwellings were to feature openings in at least three directions, two of which

were to face sunrise and sunset as is common in Iranian tradition. The project

was halted during its planning stage in 1978.

After three major design revisions between 1961 and 1964, Habitat

emerged in built form in 1967 as a series of precast, concrete units, called “boxes,”

clustered along a spine of three, hill-shaped structures, and held together by

post-tensioning, high-tension steel rods, cables, and welding. While the original designs

for Habitat conceived of 950 modular units to be plugged into a vertical “super-frame”

structure standing just over twenty storeys high, Habitat’s finished size was much more

modest in scale, numbering 354 boxes at a cost of approximately $21 million.

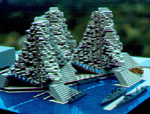

Modelled after the suspension system of a sailboat’s mast and boom,

Habitat New York II was conceived in two parts: three, fifty-storey core

structures were to house elevators and mechanical services, while modules were

to be suspended via cables from each of these structures' three projecting arms.

At the base of the complex there was to have been one million square feet of

office, retail, commercial and hotel space.

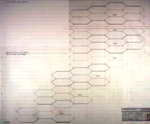

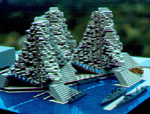

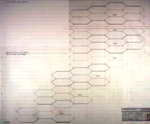

The first phase of Habitat Puerto Rico foresaw the construction of 600 to

800 hexagonal modules, arranged in clusters of 12, to form 264 dwellings set

within a steep slope overlooking San Juan. The Berwin Farm scheme was much more

modest in scale. Consisting of only 150-300 hexagonal units (also to be

clustered in groups of 12), it would have been one quarter to one half the size

of the Hato Rey plan. As in all Habitat designs, each residence at Habitat

Puerto Rico was to feature a private terrace and garden located on the roof-top

of the module below.

As Habitat housing was intended to be implemented at various sites throughout the

country, Safdie devised a modular system adaptable to different densities,

climates and topographical conditions. In all, approximately 1,500 units were

planned, ranging in size (from one to four bedrooms), and area (from 77 to 97

m sq. [829 to 1044 ft sq.]--excluding terraces). Safdie's innovative approach to meeting the

local building code (which stipulates the use of Jerusalem stone for all

building surfaces) was to combine Jerusalem stone aggregate with a concrete

mixture, and then to sandblast the finished surface (as he had done in Habitat

'67) in order to reveal the local stone. Safdie planned to use chemically

stressed lightweight concrete for this project.

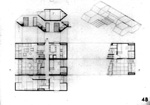

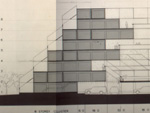

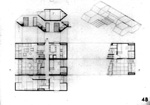

Habitat Rochester was to be a multi-storeyed complex with units arranged on

the diagonal around the perimetre of the complex’s focal point, a central

square. Additional clusters of modules radiated as extended arms from this main

configuration of dwellings. The diagonal arrangement of modules with their

slanting roofs conferred a dynamic appearance on the scheme. A series of

external pedestrian walkways were designed to link residences with the

complex’s commercial facilities. Both stairwells and elevators provided

the complex with its vertical circulation systems.

Originally Habitat Tehran was to feature 180, one-, two-, and three-bedroom

dwellings tightly clustered into a single mass on a hilly site overlooking the

city of Tehran. The scale of the project was later modified and reduced to 162

residences, a design which omitted one-bedroom units and added a supplementary

configuration of four-bedroom residences. Open-air passages with direct access

to residences were designed to be located on every four levels of the complex

(and every two in the high-rise sections). These external corridors were to be

landscaped, and to periodically open into public courts and gardens. As in all

Habitat projects, each residence also provided access to a private roof garden

which converted into an indoor greenhouse, to maximize the use of space at all

times of the year.

In Safdie’s earliest designs for Habitat ‘67, the building was to be constructed out of

rhomboid-shaped modules, a form which gave way in subsequent drawings to the simpler

geometry of rectangular boxes. Each module measures 12 m x 5.33 m x 3 m, or 56 m sq. (38 ½ ft long x 17 ½ ft wide x 10 ft high, totalling 600 ft sq.), and weighs as much as 90 tons. Habitat’s modules were all

constructed and assembled in situ: an on-site factory was used to produce concrete which

was then applied to the prefabricated steel cages that were to become Habitat’s signature

modules. The modules were then lifted into place on the main structure by crane, and

arranged in one of 16 different configurations. The concrete exteriors were sandblasted,

and no further surface treatment was added.

For both Habitat New York schemes, modules were to be

octagonal in plan and cast in “prestressed” or lightweight concrete at a local

factory and shipped along the East River to the Habitat site. In the case of

Habitat New York II, two separate octagonal modules were to be realized (each

differing in size and shape), and combined to produce numerous configurations

for single- or multi-level dwellings. For this second scheme, each unit’s

plumbing and electrical elements were to have been supplied directly through the

modules, before being routed back to a central structural core at the complex's

base.

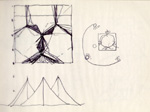

The basic shape of the modules designed

for Habitat Puerto Rico was a split-level hexagon. The geometry of the hexagon

would have provided shade to underlying residences by virtue of the way units

were to be stacked and cantilevered atop one another. Once prefabricated at a

central manufacturing plant, these light-weight, concrete units were to be

transported via truck or barge to their intended site. It was thus shipping

requirements which dictated that the width of the modules not exceed 3.6 m (12 ft)

so as not to hinder their transportation on the island’s highways.

Unlike earlier Habitat projects which featured self-contained units with no projecting volumes, the modules for Habitat Israel were conceived in two essential parts: the box and the dome. The semi-circular,

mechanized fibreglass dome that Safdie devised specifically for this project was

to be fitted into a track located at approximately two-thirds the length of the

module's principal concrete box (measuring 11.6 m x 3.6 m [38 ft x 12 ft]). This rotating dome

would have allowed each resident to control the exposure of sunlight entering their residence.

There were also subcomponents designed to be added to

the module, depending on the site's specific requirements. The Ministry of Housing had

conceived of placing various manufacturing plants throughout the country to

produce these prefabricated modules.

Like the original Habitat in Montreal, individual modules

for Habitat Rochester were designed as concrete, rectangular boxes, measuring 3.6

m x 10.9 m (12 ft x 36 ft). Units were composed of two overlapping modules

arranged at right angles to one another, creating two-storey residences with

slanting roofs for added volume and height. Each residence was also to have

featured a 3.6 m x 3.6 m (12 ft x 12 ft) garden terrace, convertible for indoor

winter use and accessible by sliding glass doors. Residences were to have ranged

from one-bedroom units measuring 56.2 m sq. (605 ft sq.), to

three-bedroom units measuring 90.6 m sq. (975 ft sq.).

As construction techniques and structural issues were never

finalized for this project throughout its two-year life span, the decision to

use a fully industrialized box system (whereby the modules would be

prefabricated and cast on site as opposed to being built according to

conventional construction methods), remained unresolved. Nevertheless, modules

were to be variations on Safdie’s signature “boxes,” most of which would be

configured into two-storey dwellings oriented around a two-level atrium.

Residences were to vary in size from two-, three-, and four-bedroom units, and

in area, from 112 m sq. to 224 m sq. (1206 to 2411 ft sq.). Habitat Tehran is the only

Habitat design not to feature one-bedroom dwellings, which were felt to be

unnecessary in a family-oriented complex.

Habitat ‘67’s remarkable engineering achievement is also one of the

building’s most distinguishing and trademark features: the very modules that cantilever out

of its three-part 290 metre (950 foot) spine are in fact themselves structural members. Each organ of

Habitat--its dwelling units, walkways, and three sets of paired elevator shafts--acts as a

loadbearing structure to the overall building. Modules were to be stacked and clustered

following principles of compression and post-tensioning. This system was devised under

the direction and guidance of Habitat’s structural engineer, Dr. A. E. Komendant.

Following the nautical principles of a sailboat’s mast and boom,

light-weight modules were to be suspended within a matrix of concrete-encased cables.

These cables were to have extended between the top of the structural core and a compression

beam at the complex’s base. Pedestrian walkways were to have originated from the

core building tower, providing access to modules flanking either side of the passage.

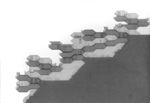

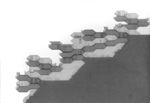

The hexagonal modules of Habitat Puerto Rico were to be clustered in groups of 12 and stacked on top of

each other in adjacent rows in honeycomb formation. Bridges were conceived to connect the

various clusters. The basic shape of the hexagon presupposed that the modules would fit

together as cantilevered loads. These loads were to be assembled by steel-cabled post-tensioning,

thereby following the same principles of compression as seen in the original Habitat ‘67.

A typical residence might include as many as three modules. The basic module’s split-levelling

was specifically designed to minimize the internal space traditionally lost to staircases.

Units were to be arranged in varying configurations of one- to four-bedroom dwellings.

The basic module of Habitat Israel was designed so as to allow

maximum versatility in its assemblage. Therefore, it would have been conceivable to have hillside

terracing or high-rise clusters for certain Israeli sites, and low-lying, two- and three-storey

houses in others, or even units located side by side. Clusters of modules were to be stacked

around a main vertical service core, and connected by pedestrian walkways. In the case of multi-levelled units, some modules were to be connected by slanting roofs.

Modules for Habitat Rochester were to be assembled in the traditional Habitat manner,

stacked and compressed in a dense cluster of residences.

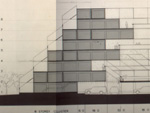

Modules were to be clustered and stacked in typical Habitat fashion, following

the natural incline of the Elahieh site’s steep slope. At its peak, clusters of modules

were to have reached 14 storeys, while the complex would have expanded outward at the hill’s

base, tapering into low-lying configurations of dwellings.

Integral to the sense of community Safdie sought to create at

Habitat are its external walkways, called “pedestrian streets,” which interconnect the

multi-levelled residential modules on five storeys (Habitat’s ground floor, plaza, and

its fifth, sixth, and tenth floors), while providing access to each residence. It is

precisely these walkways which both expose the building to the natural elements and

open into communal spaces for Habitat residents. The commercial and institutional

facilities that Safdie had originally envisioned for the project--its schools, shops,

offices and cultural spaces--never materialized. A convenience store beneath Habitat

in the complex’s 200-car underground parking lot is its only retail

operation.

Safdie’s scheme for Habitat New York II responded to the increased density criteria (300 units per acre) of its second prospective site, now in lower Manhattan at the Wall Street Pier, as well as to strict city by-laws prohibiting complete obstruction of views and access to the river. Safdie opted for an entirely different structural programme than that of Habitat New York I, one in which modules were to be grouped even more densely, not as loadbearing members, but suspended within a matrix of concrete-encased cables.

The intended location of Habitat Puerto Rico on inexpensive and

underdeveloped hilly terrain was not an insignificant reason for the project’s failure. The steepness of the

site posed particular construction problems, which added to the overall cost of the project.

Had the project succeeded, Safdie’s hexagonal modules would nevertheless have provided great

versatility for different topographical sites in the manner they could be assembled to

produce high-density living environments.

The flexibility and versatility of Safdie's design for this particular Habitat scheme meant that the project was ideally suited to any number of topographical locations indigenous to Israel. His design sought to pair potential hillside locations or low-lying areas with structures of the appropriate height and density.

Habitat Rochester was to be built on a riverside site conveniently located close to Rochester’s downtown core. The ground level was relatively flat. The main imperative was to accommodate the high number of units (1,200) within the tight spatial requirements of the U.S. Federal Housing Authority, which resulted in a density of 45 units to the acre.

Access to the chosen site for Habitat Tehran was difficult, as the project was to be constructed on a steeply sloping hill in the neighbourhood of Elahieh overlooking the city of Tehran and its nearby mountainous landscape. This particular site, located between single-family dwellings to the north and high-rise apartments to the south, conferred upon the project its major design motif. Safdie sought to relate to the site massing of both neighbouring developments, in addition to the steep topography itself, by combining high-rise towers and hillside cluster housing in a single, unified complex. From the structure’s base at the foot of the slope, units were to be stacked, increasing in density and in height as the slope itself rises.

Habitat is located on MacKay Pier (later renamed Cité du Havre), a

landfill peninsula bordered on either side by the St. Lawrence River, with views to

Montreal’s downtown area to the north, and Ile Ste-Hélène to the east. While Safdie’s main

goal in his thesis project was to establish the criteria for a housing system which could in

essence be adapted to diverse site conditions, he did nevertheless favour proximity to

downtown and a site with physical beauty. In this respect, the clustered Mediterranean

villages he recalled from his youth in Israel were of considerable influence to him.

Conforming to strict city by-laws which maintained that the

waterfront area remain visually unobstructed, the design for Habitat New York II

conceptualized the project suspended over the water, while encasing a marina, a hotel,

a vast shopping complex, offices, and parking for 3000 vehicles on the site’s lower levels.

The neighbouring area of the site was at the time undeveloped, thus permitting

Habitat’s expansion should the project be enlarged at a future date.

The first site selected for Habitat Puerto Rico was a twenty-acre lot on a 76-metre (250-foot)

high hill in the San Patricio area of San Juan known as Hato Rey. The steep slope of Hato

Rey was to have accommodated 600 to 800 housing units at 40 units per acre, thereby meeting the high density living requirements of the moderate-income

housing project. The Berwin Farm site, for which a second scheme was developed and some

construction begun, was also a hilly terrain. The designs of both schemes maximized views

of the panoramic sites, by clustering residences along the steep incline, and locating all

of the complex’s social elements--its shops, cafés, offices, outdoor amphitheatre and

14-storey high-rise towers--on the hill’s summit.

While Habitat Israel was originally conceived to be

implemented at multiple sites across the country, its 'test' site, chosen by Safdie, was an area

in Jerusalem called Manchat. This particular location provided the architect with the project's

two principal design challenges: how to create housing for hilltops (a prevalent feature in Israel)

and how to integrate innovative design with the more historic presence of existing Arab

hillside establishments. The earlier designs for Habitat Puerto Rico (1968-1970) were similarly

conceived for a hilly terrain.

The 30-acre project was to have occupied a site along the Genesee River, within walking

distance of Rochester’s downtown area. In spite of the project’s rigorous high-density

requirements (approaching 45 units to the acre), parking and landscaped recreational areas

were integral to the plan. Circulation routes were to have separated vehicular and

pedestrian traffic. Elevated, open-air walkways traversed the complex, linking residences

with the site’s commercial and recreational facilities.

Safdie’s design followed the topography of its five-and-a-half

acre site with its steep slope by building units directly along its incline. In this way,

panoramic views overlooking the city of Tehran were maximized for each unit. Particular

structural concerns arose due to the seismic conditions of the site, for which the project’s

engineering consultant, Dr. Komendant, suggested the use of U- and L-shaped modules in

place of entire boxes. Such shapes, Dr. Komendant argued, would have provided greater

stability and protection against the threat of earthquakes.

The progressive ideas that Safdie pioneered in his designs for Habitat ‘67, including the introduction of industrialized building methods such as assembly-line strategies and on-site construction, have never been developed to the scale that would render them viable for Safdie’s original goal of providing cost-effective housing. Nevertheless, Safdie continues to explore variations on the systems he first developed for

Habitat ‘67. Subsequent Habitat-inspired projects allowed Safdie to redress some of the structural challenges posed by Habitat. To reduce the stresses and forces on loadbearing structures, for example, Safdie explored different geometries for creating his “box shapes,” including tetrahedrons, octahedrons, and rhombic dodecahedrons.

The use of “prestressed” concrete, a lighter material than traditional concrete, would have allowed Safdie to build high and increase the complex’s density. Taking full advantage of the site bordering the East River, Safdie planned to cantilever certain modules over the water, thereby providing high-density environments

without infringing on available land.

Creating cost-effective housing in Puerto Rico was a preliminary requirement for the project. Specific strategies to lower building costs included the use of a hexagonal unit and a reduction in its weight from the standard 70-ton model to 22 tons; the simplification of structural systems (such as the elimination of elevators and the reduction of staircases); and the implementation of industrialized housing techniques in a central manufacturing plant for the mass-production of homes.

Habitat Israel was originally conceived to create mass-produced, low-cost housing for a country with a perpetual housing shortage. Safdie's original designs also promised the implementation of modernized building techniques where it was greatly needed.

While Habitat Rochester was not the only Habitat project to feature multi-level dwellings (Habitat Tehran and Habitat Puerto Rico were to have done so too), its modules had virtually the smallest surface plan of all Habitat projects. The particular configuration of modules into overlapping, perpendicular units was deliberately intended to give the illusion of a more spacious interior.

Strategies for this particular project evolved from cultural and climatic considerations indigenous to Tehran. Both of these exigencies were resolved through the inclusion of the atrium-court in the basic modular design. This feature respected the Iranian tradition of providing each home with an internal garden, while equally making this feature convertible to the seasons.