CRAFTSMEN AND

DECORATIVE ARTISTS

Rosalind M. Pepall

The quality of workmanship in the buildings of Edward and William Maxwell was outstanding. One reason for this was the wealth and taste of so many of their clients - people who could, and would, pay for handcrafted work by qualified artists and craftsmen in expensive imported materials. Another was the value the Maxwells placed on the collaboration between the architect and the craftsman or artist, a value that can be traced to the influence of H. H. Richardson and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts on their education and training. Like their American and French teachers, the Maxwells worked closely with the artists upon whom they relied to execute the decorative aspects of their buildings.

The contributions of the woodcarver, stone sculptor, metalworker or stained glass maker are liable to go unidentified and unrecognized unless he happens to be an artist of particular repute. In the Maxwell account books, however, the names of the participating firms, contractors and artisans are noted for every building, along with the date, type and cost of the work commissioned. These records, which provide an invaluable and rare resource with which to pinpoint the role of craftsmen in an architectural practice, also reveal the degree of respect the Maxwells accorded their work.

Edward and William Maxwell were frequently called upon to supply furnishings, wall coverings, carpets, light fixtures, fireplace accessories and, in some cases, antiques to complete a room's interior decor. Designs for interior ornament and furnishings were carefully delineated in the elevation and detail drawings of their buildings.

Because of their interest in the arts and their social connections with the Montreal art community, the Maxwell brothers were in a position to commission architectural decoration from some of the best artists and craftsmen in Canada. Among their close friends were Maurice Cullen, George Hill, Clarence Gagnon, William Hope and George Horne Russell.1 William in particular belonged to a number of art organizations, including the Pen and Pencil Club, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild and the Arts Club.2 Both brothers enjoyed painting and exhibited their canvases regularly at the Art Association of Montreal's Spring Exhibitions.

Hand-carved interior woodwork and sculpted stone exterior ornament lend elegance to a residence and indicate the prosperity of its owner. The Maxwells were fortunate to have had many prosperous clients and so sought out skilled craftsmen capable of executing this type of decorative work.

In the Maxwell records, frequent reference is made to the sculptor George Hill, with whom Edward enjoyed a long and fruitful collaboration. Born in Shipton, in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Hill received his professional training in Paris from 1889 to 1894, where he studied at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts.3 Upon returning to Canada in 1894, he opened a studio in Montreal and immediately began his association with Edward. He created a plaque of the architect and his wife in 1897 to commemorate their marriage the year before.4 Hill made models for the stone carving on some of Edward's early buildings, such as the Birks store and the Merchants Bank of Halifax, and his collaboration with the architects continued until the First World War.

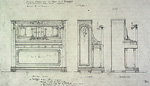

At the turn of the century, ornate, richly carved furniture in various revival styles was the fashion for the formal rooms of a house, and the Maxwells were sometimes called upon to design furniture to harmonize with a room's architecture. George Hill was responsible for the carved decoration on all of the dining room furniture made for Charles Hosmer's residence, 5 and he and probably his assistants carved the linenfolds, the tiny grotesque animals and the leaf scrolls on the wooden panelling around the room (fig. 6). When Louis-Joseph Forget asked the Maxwells to carry out major alterations to his house on Sherbrooke Street, the architects designed a piano case for the drawing room (cat. 44e). The Louis XVI cartouches, trophies and garlands that adorned the wooden panelling of this room were carried over into the design of the piano, which was painted white to match the panelling. George Hill was asked to carve the decoration on the piano, which still retains its original gilt metal music rack and candle holders .6

Hill's reputation as one of Canada's foremost sculptors in the first decades of the twentieth century is based mainly on his public monuments and war memorials. 7 One of his greatest achievements is the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument at the foot of Mount Royal Park, which he worked on from 1912 to 1914. The Maxwells designed the monument's base and laid out the square in which it stands.8

One of Hill's apprentices who later became a well-known sculptor in his own right was Elzéar Soucy. Born in Saint-Onésime, Kamouraska, he grew up in Montreal and studied sculpture there at the École du Conseil des Arts et Manufactures.9 Then, in his own words, "after three years of apprenticeship devoted to carving sitting-room armchairs in the styles of Victoria and Louis-Philippe", he joined Hill's workshop in 1898.10

Soucy was not given commissions directly by the Maxwell firm until the 1930s,11 but he had previously worked under Hill in a number of the Maxwell buildings. The work in the Hosmer house, "un véritable petit Versailles", stood out in Soucy's mind as he reminisced in later years about the thirty craftsmen who had been engaged to carve the florid wood, stone and plaster decoration in the Drummond Street residence. 12 According to Soucy, young Quebec sculptors worked alongside about ten specialists from Italy and else where in Europe who were brought to Montreal from New York, where they had been working on the John D. Rockefeller residence.13

A lesser-known sculptor who carried out carved decoration and made furniture for many of the Maxwells' major clients was Félix Routhier. 14 His name appears in the Maxwell office records from 1900 to 1914. Routhier executed the magnificent oak staircase panels in the James T Davis house for the extraordinary sum of $6,565 (cat. 39d). His skill is evident in the hand-carved pierced leaf scrolls and newel posts of the balustrade. 15

Routhier's work for the office ended just at the time the brothers began to give large commissions to the Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) Limited, the Montreal branch of the Worcestershire-based Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts, which was linked with the Arts and Crafts movement.16 The Montreal workshop opened in 1911 under the management of British architect E. Lance Wren. The Guild was no doubt encouraged to open the office by the Maxwells' commissions for the furniture and architectural sculpture for the Saskatchewan Legislative Building, the Art Association of Montreal's new gallery and the Dominion Express Company's offices on Saint James (Saint-Jacques) Street, all of which were under construction that year. 17

The Maxwells designed the workshop for the Bromsgrove Guild on Clarke Street. The building included space for "plasterwork, carvers, cabinet-makers, upholsterers and polishers, a veneering room, kiln, and an office and draughting room for Mr. Wren".18 The British firm continued for a number of years to supply the Maxwells with stained glass windows and draperies, whereas the Canadian branch executed furniture and plaster models for carving or casting. The Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) advertised that they had been responsible for "all the modelling for all ornamental work in wood, iron, bronze, plaster and stone ... as we]] as many iterns of special furniture" in the major additions to the Château Frontenac carried out by the Maxwell firm from 1920 to 1924.19

The men in the Bromsgrove Guild's Canadian workshop, most of whom were British, were considered to be the best and the most expensive cabinetmakers in Montreal. 20 Wren and his staff may have carried out some of their own furniture designs, but in their work for the Maxwells they generally followed plans supplied by the architects. Though based on historical English, French and Italian examples, the pieces were not slavish reproductions. The refined and often sumptuously carved ornament contrasted with the surfaces left undecorated to show off the wood's rich colouring and grain (fig. 7).

In addition to commissioning wood carving and furniture, the Maxwells asked artists to paint mural panels as an integral part of the interior decoration in some of their buildings. At the end of the nineteenth century, a number of Canadian artists endeavoured to promote mural painting in both public and private buildings, and a Society of Mural Decorators was formed in Toronto in 1894. 21 Its members encouraged mural painting in schools, libraries, churches and government buildings, as well as in private houses. Aware of these developments, the Maxwells commissioned artists to carry out a number of murals. These were painted not directly onto the wall, but on canvas and then glued in place. The favoured location for murals was above mantelpieces or set into the wall panelling.

Maurice Cullen was one of the Canadian artists who experimented with mural painting. Cullen had shared lodgings with William when they were both in Paris in 1899, and his studio on Beaver Hall Square was located very close to the Maxwells' architectural office. 22 The Maxwells called upon him to carry out murals in a number of their important city residences, notably the James T Davis (fig. 8) and Richard R. Mitchell houses.23 Cullen chose landscape scenes in subdued tones that harmonized with the rest of the interior decor. He did not sign his paintings, as they were considered decorations.

Frederick Challener was more prominent than Cullen as a mural painter, A founder of the Society of Mural Decorators, he promoted this art through his work and his writing. Challener understood the need for the architect and artist to "pull together" in order to integrate decorative painting with architecture. 24 He painted two murals for Maxwell houses and carried out decorations in the Royal Alexandra Hotel in Winnipeg. 25 Other artists, including Frederick Hutchison and Clarence Gagnon, also undertook the occasional commission for murals in Maxwell buildings. 26

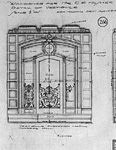

During the period when the Maxwell practice was in operation, stained glass windows were fashionable for both secular and religious buildings. 27 The Maxwell houses were often ornamented with stained glass, which added a touch of colour to transoms or cabinet cases. A few cartoon drawings for glass in William's hand remain among the Maxwell records. The firm of Castle & Son provided stained and leaded glass for a number of their houses. During the 1890s this firm was well known in Montreal - especially for its stained glass windows and church decoration. The company also developed a reputation for its fine cabinetmaking and interior furnishings. Between 1900 and 1912 the Maxwell brothers frequently ordered furniture, rugs, wallpaper and draperies from Castle & Son. A most important commission for stained glass was the two large windows the firm made in 1905-1906 for the billiard room of the L.-J. Forget house on Sherbrooke Street (cat. 44f) .28

For church windows, the Maxwells turned to the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts. The British parent provided the series of thirteen stained glass windows for the Church of the Messiah in Montreal. These were designed and executed between 1907 and about 1917 by Archibald Davies, who ran the Guild's stained glass workshops from 1906 until his death.29 These windows, all but two recently destroyed by fire, were inspired by British Arts and Crafts design, their backgrounds filled with naturalistic flowers and birds. 30

Many of the Maxwells' buildings feature exquisite metalwork in the form of wrought iron entrance door grilles, balconies and gates. Instead of buying industrially produced metal wares, the Maxwells preferred to commission handcrafted metalwork, for example the grilles wrought in scrolled leaf forms on the vestibule doors of the Hosmer house (fig. 9). Many of the designs for this decorative ironwork were drawn by William Maxwell. His year of study in Paris had undoubtedly contributed to his enthusiasm for an art in which France had long excelled.

Another craftsman, Paul Beau, who began his career as an antique dealer, supplied Maxwell clients with his own fine hand-hammered brass and copper pieces as well as the occasional antique.31 His work may be found in many of the residences, hotels and clubs designed by the Maxwell brothers.

Beau was one of the numerous craftsmen who were indebted to the Maxwells' support. William's daughter, Mary Maxwell Rabbani, recalls that her father had a close working rapport with these artisans, who "adored him".32 By taking full advantage of the skill and dedication of trained craftsmen, Edward and William Maxwell ensured the superior quality of their architecture. In recent years the reassessment of Edwardian architecture has led to a renewed appreciation for the decorative work of these artists, which was so essential a component of the Maxwell buildings.

1 Hope and Horne Russell were clients as well as friends. The houses built for William Hope, one in Montreal and one in Saint Andrews, N.B., no longer exist. William Maxwell designed a summer house for Horne Russell in Saint Andrews in 1924. Resume Text

2 Leo Cox, "Fifty Year, of Brush and Pen: A Historical Sketch of the Pen and Pencil Club of Montreal" (unpublished manuscript, 1939, in the personal records of W. S. Maxwell). The club was founded in 1890, and among the members listed were William Brymner, William Van Horne, Robert Harris, George Hill and Percy Nobbs. W. S. Maxwell joined on December 21, 1907. In 1910 he served on the General Committee of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, founded in 1906 to promote the revival of handcrafted arts. For his role in the Arts Club, see cat. entry 48. Resume Text

3 Hill (1862-1934) studied under Jean-Antonin Injalbert and Henri Michel Chapu and finally with Alexandre Falguière at the École des Beaux-Arts (undated information form filled out by George William Hill, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and scrapbook in the collection of the sculptors daughter, Dr. Eleanor Venning). Resume Text

4 In the late nineteenth century, a number of sculptors commemorated their friends and colleagues with medallions. For example, Karl Bitter made a portrait relief of his friend Richard Morris Hunt in 1895, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens presented his longtime collaborator, the architect Stanford White, with a marble relief portrait of Mrs. Bessie White as a wedding gift in 1884. Resume Text

5 [Work Costs Book F, 1899-1904], p, 45, MA, Series C. Resume Text

6 Ibid., p. 20, indicates that Hill was paid $627 for this commission on November 6, 1902. He was probably responsible for carving the wall panelling as well, for he was paid $1,369.22 in 1901 for, as noted less specifically ill the account book (p. 23), "modelling and carving Sherbrooke St". Resume Text

7 Venning scrapbook; see also Aline Gubbay, "Three Montreal Monuments: An Expression of Nationalism" (Master's thesis, Concordia University, 1978). Resume Text

8 See the essay "City Planning and Urban Beautification" in the present catalogue. Resume Text

9 Soucy (1876-1970) studied under Arthur Vincent and Louis-Philippe Hebert at the Conseil des Arts et Manufactures in Montreal, and apprenticed in the atelier of Alfred Lefrançois and Philippe Laperle. See Elzéar Soucy: sculpteur sur bois", in Jean-Marie Gauvreau, Artisans du Québec (Montreal: Les Éditions du Bien Public 1940), p. 142, and Msgr. Olivier Maurault, "Une famille de sculpteurs: Les Soucy", in Société Royale du Canada. Mémoires, 3rd series, vol. 36, section 1 (May 1942), pp. 71-76. Resume Text

10 Huguette Cléroux;, "A Study of the Works of Mr. Elzéar Soucy", with a preface by Elzéar Soucy (unpublished manuscript, Universit´ de Montréal Library School, 1961), p. iii. Soucy acquired the workshop of George Hill between 1912 and 1914, and went on to establish his reputation in church sculpture and statues of prominent public figures. See Gloria Lesser, École du Meuble 1930-1950 (Montreal: Le Château Dufresne Inc., Musée des arts décoratifs de Montréal, 1989), pp. 45-49. Resume Text

11 The Maxwells paid Soucy for a model of a Celtic cross for the J. T. Davis family on May 22, 1930 [Work Costs Book N, 1914-1915], p. 45, MA, Series C. Resume Text

12 Gauvreau, 1940, p. 145. Resume Text

13 Cléroux, 1961, p. iii. Resume Text

14 In his parish registry, Félix Routhier is referred to as a sculptor on the occasion of his marriage in 1868 (ANQM, Paroisse Notre-Dame-de-Montr´al ZQ0001-0026, Registre — Mariages, vol. 121, p. 131, no. 600, Félix Routhier and Julie Plante, November 23, 1868). It seems that he died in 1916, since the following year his wife is listed as a widow. Resume Text

15 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 284, MA, Series C. Routhier was paid in various instalments from February 15 to December 11, 1911. Resume Text

16 See Alan Crawford, By Hammer and Hand: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Birmingham (Birmingham: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, 1984), pp. 32-33. Resume Text

17 For an account of the work of the Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) in the AAM Art Gallery, see Rosalind M. Pepall, Construction d'un musée Beaux-Arts/Building a Beaux-Arts Museum, exhib. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1986), pp. 75-82. Resume Text

18 Project no. 46.0, "Bromsgrove Guild and Lumber", undated, MA. Resume Text

19 Construction, vol. 18 (August 1925), p. 17. Resume Text

20 Telephone interviews by the author with Hugh Illsley, April 15, 1985, and Richard Bolton, May 28, 1985. Resume Text

21 For background on the Canadian mural movement, see Rosalind M, Pepall, "The Murals in the Toronto Municipal Buildings: George Reid's Debt to Puvis de Chavannes", The Journal of Canadian Art History, vol. 9, no.2 (1986), pp. 142-160. Resume Text

22 Maurice Cullen (1866-1934) returned to Montreal in 1902, and from 1906 his studio was at 3 Beaver Hall Square. The Maxwells' office was at 6 Beaver Hall Square. Resume Text

23 See cat. entries 39 and 36. Cullen carried out a large decorative panel for the L.H. Timmins residence in Westmount in 1913 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 351, MA, Series C). Resume Text

24 See Frederick Challener, "Mural Decoration", CAB, vol. 17 (May 1904), pp, 90-92. Resume Text

25 For the Maxwells, he undertook a major "Painting Decoration" for Dr. Milton Hersey's residence on Rosemount Avenue in Westmount (demolished) about 1910-1911, for which he was paid $300 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 133, MA, Series C). For F. Howard Wilson's Sainte-Agathe house, Challener paineda mural over the mantel for $50 August 22, 1911 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 297, MA, Series C). Resume Text

26 Frederick W. Hutchison (1871-1953) painted a mural decoration on the ceiling of the "reception room" for Charles Hosmer in 1902 ([Work Costs Book F, 1899-1904], p.42, MA, Series C). Clarence Gagnon is recorded as executing "2 decorative panels" for the Eugène Lafleur house on Peel Street, January 7, 1903 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p.141, MA Series C), as well as stencilled decoration in the Clouston house, Senneville, and the chapel of the Forget house, also in that area, in the summer of 1903 ([Work Costs Book F. 1899-1904], pp. 24, 52, MA, Series C). William Clapp carried out a painted decoration in the Dominion Express Company Building in 1912 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 168, MA, Series C). Resume Text

27 See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, "A New Renaissance: Stained Glass in the Aesthetic Period" , in In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement, exhib. cat. (New York: Rizzoli, 1986), pp. 176 -197. Resume Text

28 "The Maxwells paid Castle & Son $600 for the two windows, April 18, 1906 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 189, MA, Series C ). Resume Text

29 The work of Davies (1878-1953) is mentioned briefly in Crawford, 1984, p. 126. Orders for the windows are listed in [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 261, MA, Series C. See also Nevil Norton Evans, Memorials and other Gifts in the Church of the Messiah, Montreal (Montreal, 1943). Resume Text

30 Two illustrations of this major commission by Davies appeared in "British Stained Glass", in Studio year Book of Decorative Art (London: The Studio, 1910), pp. 46, 111. Resume Text

31 See Rosalind M. Pepall, Paul Beau (1871- 1949) (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1982). Resume Text

32 Interview with Mary Maxwell Rabbani by France Gagnon Pratte and the author, April 1, 1989, Haifa. Resume Text

Rosalind M. Pepall

The quality of workmanship in the buildings of Edward and William Maxwell was outstanding. One reason for this was the wealth and taste of so many of their clients - people who could, and would, pay for handcrafted work by qualified artists and craftsmen in expensive imported materials. Another was the value the Maxwells placed on the collaboration between the architect and the craftsman or artist, a value that can be traced to the influence of H. H. Richardson and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts on their education and training. Like their American and French teachers, the Maxwells worked closely with the artists upon whom they relied to execute the decorative aspects of their buildings.

The contributions of the woodcarver, stone sculptor, metalworker or stained glass maker are liable to go unidentified and unrecognized unless he happens to be an artist of particular repute. In the Maxwell account books, however, the names of the participating firms, contractors and artisans are noted for every building, along with the date, type and cost of the work commissioned. These records, which provide an invaluable and rare resource with which to pinpoint the role of craftsmen in an architectural practice, also reveal the degree of respect the Maxwells accorded their work.

Edward and William Maxwell were frequently called upon to supply furnishings, wall coverings, carpets, light fixtures, fireplace accessories and, in some cases, antiques to complete a room's interior decor. Designs for interior ornament and furnishings were carefully delineated in the elevation and detail drawings of their buildings.

Because of their interest in the arts and their social connections with the Montreal art community, the Maxwell brothers were in a position to commission architectural decoration from some of the best artists and craftsmen in Canada. Among their close friends were Maurice Cullen, George Hill, Clarence Gagnon, William Hope and George Horne Russell.1 William in particular belonged to a number of art organizations, including the Pen and Pencil Club, the Canadian Handicrafts Guild and the Arts Club.2 Both brothers enjoyed painting and exhibited their canvases regularly at the Art Association of Montreal's Spring Exhibitions.

Hand-carved interior woodwork and sculpted stone exterior ornament lend elegance to a residence and indicate the prosperity of its owner. The Maxwells were fortunate to have had many prosperous clients and so sought out skilled craftsmen capable of executing this type of decorative work.

In the Maxwell records, frequent reference is made to the sculptor George Hill, with whom Edward enjoyed a long and fruitful collaboration. Born in Shipton, in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, Hill received his professional training in Paris from 1889 to 1894, where he studied at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts.3 Upon returning to Canada in 1894, he opened a studio in Montreal and immediately began his association with Edward. He created a plaque of the architect and his wife in 1897 to commemorate their marriage the year before.4 Hill made models for the stone carving on some of Edward's early buildings, such as the Birks store and the Merchants Bank of Halifax, and his collaboration with the architects continued until the First World War.

At the turn of the century, ornate, richly carved furniture in various revival styles was the fashion for the formal rooms of a house, and the Maxwells were sometimes called upon to design furniture to harmonize with a room's architecture. George Hill was responsible for the carved decoration on all of the dining room furniture made for Charles Hosmer's residence, 5 and he and probably his assistants carved the linenfolds, the tiny grotesque animals and the leaf scrolls on the wooden panelling around the room (fig. 6). When Louis-Joseph Forget asked the Maxwells to carry out major alterations to his house on Sherbrooke Street, the architects designed a piano case for the drawing room (cat. 44e). The Louis XVI cartouches, trophies and garlands that adorned the wooden panelling of this room were carried over into the design of the piano, which was painted white to match the panelling. George Hill was asked to carve the decoration on the piano, which still retains its original gilt metal music rack and candle holders .6

Hill's reputation as one of Canada's foremost sculptors in the first decades of the twentieth century is based mainly on his public monuments and war memorials. 7 One of his greatest achievements is the Sir George-Étienne Cartier monument at the foot of Mount Royal Park, which he worked on from 1912 to 1914. The Maxwells designed the monument's base and laid out the square in which it stands.8

One of Hill's apprentices who later became a well-known sculptor in his own right was Elzéar Soucy. Born in Saint-Onésime, Kamouraska, he grew up in Montreal and studied sculpture there at the École du Conseil des Arts et Manufactures.9 Then, in his own words, "after three years of apprenticeship devoted to carving sitting-room armchairs in the styles of Victoria and Louis-Philippe", he joined Hill's workshop in 1898.10

Soucy was not given commissions directly by the Maxwell firm until the 1930s,11 but he had previously worked under Hill in a number of the Maxwell buildings. The work in the Hosmer house, "un véritable petit Versailles", stood out in Soucy's mind as he reminisced in later years about the thirty craftsmen who had been engaged to carve the florid wood, stone and plaster decoration in the Drummond Street residence. 12 According to Soucy, young Quebec sculptors worked alongside about ten specialists from Italy and else where in Europe who were brought to Montreal from New York, where they had been working on the John D. Rockefeller residence.13

A lesser-known sculptor who carried out carved decoration and made furniture for many of the Maxwells' major clients was Félix Routhier. 14 His name appears in the Maxwell office records from 1900 to 1914. Routhier executed the magnificent oak staircase panels in the James T Davis house for the extraordinary sum of $6,565 (cat. 39d). His skill is evident in the hand-carved pierced leaf scrolls and newel posts of the balustrade. 15

Routhier's work for the office ended just at the time the brothers began to give large commissions to the Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) Limited, the Montreal branch of the Worcestershire-based Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts, which was linked with the Arts and Crafts movement.16 The Montreal workshop opened in 1911 under the management of British architect E. Lance Wren. The Guild was no doubt encouraged to open the office by the Maxwells' commissions for the furniture and architectural sculpture for the Saskatchewan Legislative Building, the Art Association of Montreal's new gallery and the Dominion Express Company's offices on Saint James (Saint-Jacques) Street, all of which were under construction that year. 17

The Maxwells designed the workshop for the Bromsgrove Guild on Clarke Street. The building included space for "plasterwork, carvers, cabinet-makers, upholsterers and polishers, a veneering room, kiln, and an office and draughting room for Mr. Wren".18 The British firm continued for a number of years to supply the Maxwells with stained glass windows and draperies, whereas the Canadian branch executed furniture and plaster models for carving or casting. The Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) advertised that they had been responsible for "all the modelling for all ornamental work in wood, iron, bronze, plaster and stone ... as we]] as many iterns of special furniture" in the major additions to the Château Frontenac carried out by the Maxwell firm from 1920 to 1924.19

The men in the Bromsgrove Guild's Canadian workshop, most of whom were British, were considered to be the best and the most expensive cabinetmakers in Montreal. 20 Wren and his staff may have carried out some of their own furniture designs, but in their work for the Maxwells they generally followed plans supplied by the architects. Though based on historical English, French and Italian examples, the pieces were not slavish reproductions. The refined and often sumptuously carved ornament contrasted with the surfaces left undecorated to show off the wood's rich colouring and grain (fig. 7).

In addition to commissioning wood carving and furniture, the Maxwells asked artists to paint mural panels as an integral part of the interior decoration in some of their buildings. At the end of the nineteenth century, a number of Canadian artists endeavoured to promote mural painting in both public and private buildings, and a Society of Mural Decorators was formed in Toronto in 1894. 21 Its members encouraged mural painting in schools, libraries, churches and government buildings, as well as in private houses. Aware of these developments, the Maxwells commissioned artists to carry out a number of murals. These were painted not directly onto the wall, but on canvas and then glued in place. The favoured location for murals was above mantelpieces or set into the wall panelling.

Maurice Cullen was one of the Canadian artists who experimented with mural painting. Cullen had shared lodgings with William when they were both in Paris in 1899, and his studio on Beaver Hall Square was located very close to the Maxwells' architectural office. 22 The Maxwells called upon him to carry out murals in a number of their important city residences, notably the James T Davis (fig. 8) and Richard R. Mitchell houses.23 Cullen chose landscape scenes in subdued tones that harmonized with the rest of the interior decor. He did not sign his paintings, as they were considered decorations.

Frederick Challener was more prominent than Cullen as a mural painter, A founder of the Society of Mural Decorators, he promoted this art through his work and his writing. Challener understood the need for the architect and artist to "pull together" in order to integrate decorative painting with architecture. 24 He painted two murals for Maxwell houses and carried out decorations in the Royal Alexandra Hotel in Winnipeg. 25 Other artists, including Frederick Hutchison and Clarence Gagnon, also undertook the occasional commission for murals in Maxwell buildings. 26

During the period when the Maxwell practice was in operation, stained glass windows were fashionable for both secular and religious buildings. 27 The Maxwell houses were often ornamented with stained glass, which added a touch of colour to transoms or cabinet cases. A few cartoon drawings for glass in William's hand remain among the Maxwell records. The firm of Castle & Son provided stained and leaded glass for a number of their houses. During the 1890s this firm was well known in Montreal - especially for its stained glass windows and church decoration. The company also developed a reputation for its fine cabinetmaking and interior furnishings. Between 1900 and 1912 the Maxwell brothers frequently ordered furniture, rugs, wallpaper and draperies from Castle & Son. A most important commission for stained glass was the two large windows the firm made in 1905-1906 for the billiard room of the L.-J. Forget house on Sherbrooke Street (cat. 44f) .28

For church windows, the Maxwells turned to the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Arts. The British parent provided the series of thirteen stained glass windows for the Church of the Messiah in Montreal. These were designed and executed between 1907 and about 1917 by Archibald Davies, who ran the Guild's stained glass workshops from 1906 until his death.29 These windows, all but two recently destroyed by fire, were inspired by British Arts and Crafts design, their backgrounds filled with naturalistic flowers and birds. 30

Many of the Maxwells' buildings feature exquisite metalwork in the form of wrought iron entrance door grilles, balconies and gates. Instead of buying industrially produced metal wares, the Maxwells preferred to commission handcrafted metalwork, for example the grilles wrought in scrolled leaf forms on the vestibule doors of the Hosmer house (fig. 9). Many of the designs for this decorative ironwork were drawn by William Maxwell. His year of study in Paris had undoubtedly contributed to his enthusiasm for an art in which France had long excelled.

Another craftsman, Paul Beau, who began his career as an antique dealer, supplied Maxwell clients with his own fine hand-hammered brass and copper pieces as well as the occasional antique.31 His work may be found in many of the residences, hotels and clubs designed by the Maxwell brothers.

Beau was one of the numerous craftsmen who were indebted to the Maxwells' support. William's daughter, Mary Maxwell Rabbani, recalls that her father had a close working rapport with these artisans, who "adored him".32 By taking full advantage of the skill and dedication of trained craftsmen, Edward and William Maxwell ensured the superior quality of their architecture. In recent years the reassessment of Edwardian architecture has led to a renewed appreciation for the decorative work of these artists, which was so essential a component of the Maxwell buildings.

1 Hope and Horne Russell were clients as well as friends. The houses built for William Hope, one in Montreal and one in Saint Andrews, N.B., no longer exist. William Maxwell designed a summer house for Horne Russell in Saint Andrews in 1924. Resume Text

2 Leo Cox, "Fifty Year, of Brush and Pen: A Historical Sketch of the Pen and Pencil Club of Montreal" (unpublished manuscript, 1939, in the personal records of W. S. Maxwell). The club was founded in 1890, and among the members listed were William Brymner, William Van Horne, Robert Harris, George Hill and Percy Nobbs. W. S. Maxwell joined on December 21, 1907. In 1910 he served on the General Committee of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, founded in 1906 to promote the revival of handcrafted arts. For his role in the Arts Club, see cat. entry 48. Resume Text

3 Hill (1862-1934) studied under Jean-Antonin Injalbert and Henri Michel Chapu and finally with Alexandre Falguière at the École des Beaux-Arts (undated information form filled out by George William Hill, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, and scrapbook in the collection of the sculptors daughter, Dr. Eleanor Venning). Resume Text

4 In the late nineteenth century, a number of sculptors commemorated their friends and colleagues with medallions. For example, Karl Bitter made a portrait relief of his friend Richard Morris Hunt in 1895, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens presented his longtime collaborator, the architect Stanford White, with a marble relief portrait of Mrs. Bessie White as a wedding gift in 1884. Resume Text

5 [Work Costs Book F, 1899-1904], p, 45, MA, Series C. Resume Text

6 Ibid., p. 20, indicates that Hill was paid $627 for this commission on November 6, 1902. He was probably responsible for carving the wall panelling as well, for he was paid $1,369.22 in 1901 for, as noted less specifically ill the account book (p. 23), "modelling and carving Sherbrooke St". Resume Text

7 Venning scrapbook; see also Aline Gubbay, "Three Montreal Monuments: An Expression of Nationalism" (Master's thesis, Concordia University, 1978). Resume Text

8 See the essay "City Planning and Urban Beautification" in the present catalogue. Resume Text

9 Soucy (1876-1970) studied under Arthur Vincent and Louis-Philippe Hebert at the Conseil des Arts et Manufactures in Montreal, and apprenticed in the atelier of Alfred Lefrançois and Philippe Laperle. See Elzéar Soucy: sculpteur sur bois", in Jean-Marie Gauvreau, Artisans du Québec (Montreal: Les Éditions du Bien Public 1940), p. 142, and Msgr. Olivier Maurault, "Une famille de sculpteurs: Les Soucy", in Société Royale du Canada. Mémoires, 3rd series, vol. 36, section 1 (May 1942), pp. 71-76. Resume Text

10 Huguette Cléroux;, "A Study of the Works of Mr. Elzéar Soucy", with a preface by Elzéar Soucy (unpublished manuscript, Universit´ de Montréal Library School, 1961), p. iii. Soucy acquired the workshop of George Hill between 1912 and 1914, and went on to establish his reputation in church sculpture and statues of prominent public figures. See Gloria Lesser, École du Meuble 1930-1950 (Montreal: Le Château Dufresne Inc., Musée des arts décoratifs de Montréal, 1989), pp. 45-49. Resume Text

11 The Maxwells paid Soucy for a model of a Celtic cross for the J. T. Davis family on May 22, 1930 [Work Costs Book N, 1914-1915], p. 45, MA, Series C. Resume Text

12 Gauvreau, 1940, p. 145. Resume Text

13 Cléroux, 1961, p. iii. Resume Text

14 In his parish registry, Félix Routhier is referred to as a sculptor on the occasion of his marriage in 1868 (ANQM, Paroisse Notre-Dame-de-Montr´al ZQ0001-0026, Registre — Mariages, vol. 121, p. 131, no. 600, Félix Routhier and Julie Plante, November 23, 1868). It seems that he died in 1916, since the following year his wife is listed as a widow. Resume Text

15 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 284, MA, Series C. Routhier was paid in various instalments from February 15 to December 11, 1911. Resume Text

16 See Alan Crawford, By Hammer and Hand: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Birmingham (Birmingham: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, 1984), pp. 32-33. Resume Text

17 For an account of the work of the Bromsgrove Guild (Canada) in the AAM Art Gallery, see Rosalind M. Pepall, Construction d'un musée Beaux-Arts/Building a Beaux-Arts Museum, exhib. cat. (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1986), pp. 75-82. Resume Text

18 Project no. 46.0, "Bromsgrove Guild and Lumber", undated, MA. Resume Text

19 Construction, vol. 18 (August 1925), p. 17. Resume Text

20 Telephone interviews by the author with Hugh Illsley, April 15, 1985, and Richard Bolton, May 28, 1985. Resume Text

21 For background on the Canadian mural movement, see Rosalind M, Pepall, "The Murals in the Toronto Municipal Buildings: George Reid's Debt to Puvis de Chavannes", The Journal of Canadian Art History, vol. 9, no.2 (1986), pp. 142-160. Resume Text

22 Maurice Cullen (1866-1934) returned to Montreal in 1902, and from 1906 his studio was at 3 Beaver Hall Square. The Maxwells' office was at 6 Beaver Hall Square. Resume Text

23 See cat. entries 39 and 36. Cullen carried out a large decorative panel for the L.H. Timmins residence in Westmount in 1913 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 351, MA, Series C). Resume Text

24 See Frederick Challener, "Mural Decoration", CAB, vol. 17 (May 1904), pp, 90-92. Resume Text

25 For the Maxwells, he undertook a major "Painting Decoration" for Dr. Milton Hersey's residence on Rosemount Avenue in Westmount (demolished) about 1910-1911, for which he was paid $300 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 133, MA, Series C). For F. Howard Wilson's Sainte-Agathe house, Challener paineda mural over the mantel for $50 August 22, 1911 [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 297, MA, Series C). Resume Text

26 Frederick W. Hutchison (1871-1953) painted a mural decoration on the ceiling of the "reception room" for Charles Hosmer in 1902 ([Work Costs Book F, 1899-1904], p.42, MA, Series C). Clarence Gagnon is recorded as executing "2 decorative panels" for the Eugène Lafleur house on Peel Street, January 7, 1903 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p.141, MA Series C), as well as stencilled decoration in the Clouston house, Senneville, and the chapel of the Forget house, also in that area, in the summer of 1903 ([Work Costs Book F. 1899-1904], pp. 24, 52, MA, Series C). William Clapp carried out a painted decoration in the Dominion Express Company Building in 1912 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 168, MA, Series C). Resume Text

27 See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, "A New Renaissance: Stained Glass in the Aesthetic Period" , in In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement, exhib. cat. (New York: Rizzoli, 1986), pp. 176 -197. Resume Text

28 "The Maxwells paid Castle & Son $600 for the two windows, April 18, 1906 ([Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 189, MA, Series C ). Resume Text

29 The work of Davies (1878-1953) is mentioned briefly in Crawford, 1984, p. 126. Orders for the windows are listed in [Work Costs Book M, 1904-1914], p. 261, MA, Series C. See also Nevil Norton Evans, Memorials and other Gifts in the Church of the Messiah, Montreal (Montreal, 1943). Resume Text

30 Two illustrations of this major commission by Davies appeared in "British Stained Glass", in Studio year Book of Decorative Art (London: The Studio, 1910), pp. 46, 111. Resume Text

31 See Rosalind M. Pepall, Paul Beau (1871- 1949) (Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1982). Resume Text

32 Interview with Mary Maxwell Rabbani by France Gagnon Pratte and the author, April 1, 1989, Haifa. Resume Text

Fig. 6. Brian Merrett, Detail of dining room panelling in Hosmer House,1991. Montreal, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Cat. 44e.Elevations for a piano case for the Louis-Joseph Forget House (Sherbrooke Street Montreal)

Cat. 39d.Main Hall and staircase, James T. Davis House

Fig. 7. Photographer unknown, Dining room table in Davis House,undated. Private collection.

Fig. 8. Brian Merrett,Mural by Maurice Cullen in billiard room of Davis House,1991. Montreal, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Cat. 44f. Stained glass window from the Louis-Joseph Forget House (Sherbrooke Street, Montreal)

Fig. 9. Edward Maxwell, Vestibule detail for Hosmer House,undated. Montreal, McGill University, Canadian Architecture Collection.